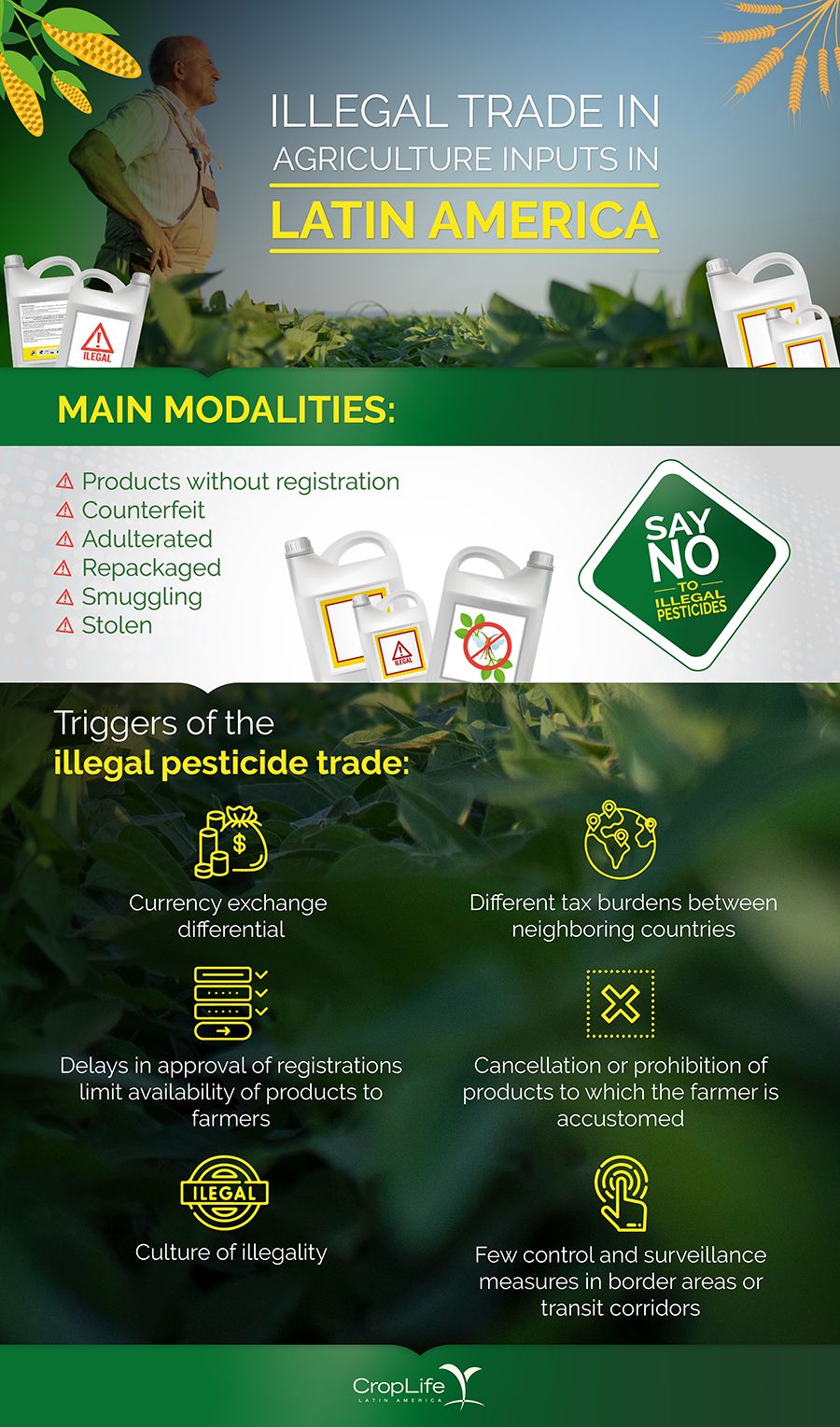

Products without registration, counterfeit, adulterated, repackaged, contraband or stolen are the modalities of illegal trade of agricultural inputs in Latin America, as confirmed by CropLife Latin America, which leads an awareness campaign against this crime that affects health, the environment and the economy.

December 07, 2021

Among the triggers and catalysts of illegality there are causes that range from the differential in currency exchange rates or tax tariffs between neighboring countries, delays in registration processes that prevent the availability of products to farmers, or cancellations or prohibitions of products that are still desired by the farmer. For example, a particular Inter-institutional Commission for the issue of illegal agrochemicals in Costa Rica that interacts with the Cámara de Insumos Agropecuarios (Chamber of Agricultural Inputs), recognizes the delay in registrations as a factor. CultiVida in Peru has no doubt that smuggling in northern Peru is due to differences in tax charges on agrochemicals in its country, as well as the recent ban on widely used products. For the Colombian association, Procultivos-ANDI, it is clear that where there is a shortage, there is an opportunity for illegality.

A recurring challenge for the industry is the measurement of an activity that by definition is obscure, hidden. The National Associations have used different approaches to quantify the magnitude of the problem. A study commissioned by APIA in Bolivia, carried out with the help of CropLife Latin America, found that illegal trade in that country amounts to 45 million dollars, equivalent to 14% of product imports to that country. PROCCYT in Mexico commissioned a study with a human rights NGO, also with support from CropLife Latin America. The estimate of the problem in Aztec ground was 20% of the market captured by illegality, equivalent to thinking that 1 in 5 products in the field is illegal. The study provided an angle of rights infringement due to the culture of illegality.

For its part ANDI-Procultivos carried out a qualitative study by characterization and is confident that a new investigation, now on the offer on digital platforms, will yield more valuable information to view the buyer as a victim. Because quantifying is difficult and expensive, associations turn to ingenuity and creativity. For example, AGREQUIMA in Guatemala monitors the collection in collection centers of its CampoLimpio program. The sampling shows a 15% return of illegal containers and serves to raise the awareness with the authorities with which it collaborates in the inspection of agroservices.

Practically all the associations in Latin America hold collaborative dialogues with their authorities with different results. APIA in Bolivia had the most recent result in seizures, with 176 tons in September 2021, as a result of inspection programs. Likewise, an operation in Colombia with 19 raids, 50 tons of seized product and 10 arrests is also striking. Judicial authorities are prosecuting offenders, moving rapidly into deeper investigations and laying down responsibilities.

The success of these operations raises the question of storage and disposal of the seized product. It helps to have a clear road map. This is what the authority pointed out to CAMAGRO in Uruguay. CropLife Latin America has guides for associations and companies on how to proceed.

CropLife Brasil carries out a successful inspection and seizure program. In 2021 alone, it accounts for 214 tons seized, 132 of which it has incinerated. However, challenges persist in working with state and federal authorities, where sometimes the mobilization of seized product itself between Brazilian states for destruction is made difficult by environmental regulations.

Another detected trend is the illegal trade on digital platforms. ANDI in Colombia is already working on its quantification and it may be that the same platforms collaborate with the destruction of seized material, as has happened in Paraná, Brazil. CASAFE in Argentina has also been successful in its collaboration with the SENASA authority and MERCADO LIBRE to remove suppliers of illegal products through the networks. Although it was not a panelist, AFAQUIMA in Venezuela constantly monitors the virtual space and alerts the INSAI of illegal offers on platforms with abundant detail to reach the offender.

Complaint mechanisms have been another strategy implemented by the network. CAFYF in Paraguay has been a leader in its collaboration with authorities, starting with a complaint channel on its own website, and then extending it to the authorities' portals. AGREQUIMA in Guatemala has also been successful in connecting its anonymous reporting channel with the authority, this through an application called PIA that allows georeferencing offered products of dubious origin. In this way, the authorities can take immediate action against criminals, or better plan the control routes to find the illegal product. The App is available to the general public. For its part, PROCCYT in Mexico accompanies the legal complaints that are made, currently 8, thanks to a good categorization of violations of laws and crimes that allows them to act precisely.

CropLife Latin America and its affiliates highlight the value of communication to raise awareness, because it prevents crime and encourages authorities to take action. Roadside billboards, radio spots, flyers and posters, radio programs, videos, and modules within farmer training programs are part of the range of tools developed in Latin America to combat the illegal trade in agricultural inputs. CAFYF in Paraguay is an association that has used all these communication pieces throughout its program. Taking advantage of national campaigns against illegality has been key, highlighted PROCCYT and ANDI-PROCULTIVOS during the meeting.